-

A complex area of some 2500ha of moorland, woodland and pasture of varied geology in North Northumberland was surveyed for Natural England to budget and on time. The standard required was high: to support the notification of a proposed Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI), a land designation with legal implications.

I offered the client a flexible approach, with scoping and subsequent inclusion of areas peripheral to the core brief, so that the work was as comprehensive as possible. Species-work and the identification of hydrological boundaries for the bogs on the site complemented the NVC map; boundary proposals were also made, with all spatial data submitted in GIS format. The work culminated in the drafting of the SSSI citation, and notification of the Bewick & Beanley Moors SSSI in June 2010, largely using the boundary I had proposed.

-

My knowledge of moorland management and experience in management-planning resulted in award of a contract to prepare a moorland burning plan to support an HLS agreement on this site.

I assessed historical practice and the context provided by other moorlands in North-east England before considering the sensitivity to fire of the complex mix of vegetation, uncommon breeding birds and scheduled archaeological features present. Great importance was attached to a document which was thorough, yet accessible and practical for a range of users, including nine separate graziers. One element of practicality was to build in flexibility across the ten-year lifespan of the agreement to accommodate the vagaries of climate, whilst stipulating tailored burning quotas for each party.

Not being the statutory representative, the work required a balanced knowledge of the issues around burning practice, recent policy initiatives, the sensitivity of species and the wishes of all the different parties involved in order to produce a document credible to all with which to commence negotiations.

-

Following the blocking of moorland drains, I designed and implemented monitoring to assess the recovery of blanket bog in the North Pennines. This internationally-important habitat plays a vital role in water supply and carbon sequestration, but the drains cut into the peat in the 1970's are thought to be impairing these functions. Although the method was initially required to mirror that deployed on the United Utilities SCaMP work in the Peak District, I decided a complementary approach was necessary in view of the particular circumstances operating on this site.

Partitioned, random quadrats are being used to record frequency of bog species pre- and post-grip-blocking, revealing some statistically-significant changes after four years. For example there has been spread of the bog-moss Sphagnum fallax in bogpools, spread of poor-fen species such as common sedge and velvet bent along the blocked grips themselves, and increases in frequency of leafy liverworts on north-facing grip-banks. Work is ongoing.

-

With the publication of the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) in 1994, the focus of conservation effort has been shifting toward BAP habitat throughout Britain. This has included a devolution to local levels and in 2011 I was awarded a contract to map BAP habitat in and around a series of 18th century enclosure roads in the parish of Lanchester, County Durham. This work entails survey, partly delivered through the motivation and training of volunteers, GIS mapping and management recommendations aimed at preserving some of the last relicts of ancient pasture and heathland in the area.

-

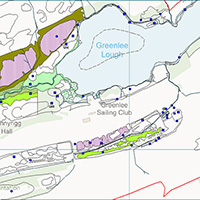

The map extract below shows a small section of the plant communities present across the cuesta landscape in the environs of the Loughs North of Hadrian's Wall, Northumberland. These were investigated as part of a check on a national inventory of fens and flushes. The locality, not previously subject to detailed vegetation work, revealed exceptional diversity and richness over wide areas. This included extended hydroseres (natural developmental sequences of ancient wetland plant communities, now very rare in England) and new populations of species of note, such as the elusive and charismatic Slender Sedge.

Contains Ordnance Survey Data © Crown copyright and database right 2011 -

Insight, planning, and a thorough knowledge of moorland ecosystems permitted delivery of a huge CSM contract into blanket bog and heath condition over nearly 5,000 ha of the Lune Forest SSSI during a three-month period in winter 2009. These high-altitude, heterogenous bogs required efficient daily coverage without compromising the identification of sometimes very localised areas of high quality sensitive to management. Due consideration to health and safety meant that the work was delivered safely, in spite of its remoteness and winter weather.

-

Since 2012 I have been working in partnership with the Botanical Society of Britain & Ireland (BSBI) to improve understanding of the famous rare plants of Upper Teesdale, and consolidate relationships between the National Nature Reserve and the numerous botanists who work in the area, many of them voluntarily. Although this celebrated locality has been a focus for the activities of botanists for centuries, its extent and richness, and the differing objectives of different recorders, has in fact yielded patchy overall coverage and poor access to records for those who need them most: the staff charged with the management of the reserve.

A trawl of BSBI records was merged with Natural England's own data before editing yielded an up-to-date inventory, presented in GIS files such as that figured in the map below. Several gaps in coverage were revealed in this way, which have since stimulated fresh recorder effort and significant finds. Alongside the GIS work A Rare Plant Conspectus was produced, a series of autecological accounts serving as a comprehensive up-to-date reference for staff and a tool with which to stimulate volunteer recorder effort.

Mapping species of conservation concern can be a vital aid to surveillance, though differing patch-sizes can create problems in presenting the data. Individuals can be depicted using symbols, but over wider areas the use of grid-squares at a 100 x 100m or 10 x 10m level may be appropriate as illustrated here in green for bearberry Arctostaphylos uva-ursi in Upper Teesdale. Where data is comprehensive enough, detailed ranges may be plotted as shown in red for a second species, alpine bistort Persicaria vivipara (original data courtesy of Dr M E Bradshaw and the students of the extra-mural department of Durham University, plotted onto an NVC map compiled by the author).

Contains Ordnance Survey Data © Crown copyright and database right 2011. -

An enjoyable departure from the norm since 2012 has been assisting The Zoological Society Of London in understanding how a zoo can support native biodiversity alongside its more familiar role - that of housing a collection of large and exotic animals for conservation and educational purposes.

The chalk downland of Whipsnade Zoo, home to the well-known White Lion Carving, is part of an SSSI, but the nationally-significant flower-rich turf had suffered owing to the increasing numbers of wallabies and mara which had been grazing there since the 1960's. Drawing on my considerable experience of the English chalk, I was able to offer insight into and guidance for the restoration programme. Monitoring is now showing how the downland is healing under a more sympathetic grazing regime, as formerly suppressed wild plants tentatively extend new shoots, and new individuals arise from seed.

Mapping the vegetation of the less-studied parts of Whipsnade occasionally required bison, rhinos and other extraordinary herbivores to be temporarily removed, but it did permit the identification of those areas with the greatest scope for biodiversity enhancement. Principal amongst these were two small, neglected woodlands whose chequered histories were further exposed through searches in the County Archive. I showed how a lost mediaeval rabbit warren shed light on the ancient credentials of these woodlands, and suggested ways forward that would sensitively conserve them.

-

Touring eleven different venues over two years to deliver niche field-skills training was one of the most rewarding work experiences I have had for a long time. Coronation Meadows is a partnership project delivered by the Wildlife Trusts, Plantlife and the Rare Breeds Survival Trust, chiefly running from 2013 to 2016. Its most important aim was to instigate county-based meadow restoration projects, each seeded, literally and metaphorically, from an outstanding, loved old meadow grassland (the so-called 'Coronation Meadow').

Meadows are the products of traditional farming practices, and although in the 21st century we recognise their value to wildlife and society, the systems which created them have largely disappeared: they are beautiful anachronisms. It was a challenge to adapt to the particular circumstances of each venue, with their widely-differing regional floras and range of student ability. I placed high emphasis on enthusing delegates whilst training them in a monitoring method designed to gauge the success of the restoration programme.

-

More than any other estuary or stretch of coast, the Tees bears evidence of the interplay between nature and human use and abuse. I was fortunate in 2015 and again in 2017 to spend time studying the vegetation at Teesmouth in a contract to Natural England aimed at reviewing the protection afforded this proud, relict tract of countryside where Yorkshire meets the north-east.

Everywhere seemed to have a story to tell. Unprepossessing grazing marshes reclaimed from the sea in past centuries illustrated a fascinating sequence of de-salinisation; what masqueraded as orchid-rich dune-slacks were either former salt-marshes or the damp plains left after nineteenth-century industrialists stripped them of sand. Unsurprisingly, none of the habitats present was as pristine as those of our undeveloped coasts, but they were a vivid illustration of how, if given the space to do so, ecosystems can adapt to massive human disruption whilst retaining much of their nature conservation value.

-

Travelling to Armenia in the summer of 2017 to join a small group compiling a baseline survey of a new national park was an unlooked-for privilege. The Jermuk National Park, an area of around 180 km² of submontane and alpine grassland with oak and steppe woodland, has been proposed in mitigation for the development of the nearby Amulsar gold-mine.

I used a knowledge of the Russian language, and memories of an earlier trip to the Caucasus in 1994 to assist the group in getting to grips with fabulous vegetation which sometimes looked familiar, sometimes had us stumped, but always took our breath away. Transposing skills in condition assessment from UK practice allowed me to gauge the ecological health of the vegetation even though its constituent species were not all familiar.

-

All credit to the Wales Wild Land Foundation for securing a 125-year lease on this mountain in north Ceredigion following a concerted fundraising appeal. Bwlch Corog will be home to the visionary Coetir Anian, or Cambrian Wildwood. At a time of unparalleled interest in alternatives to the intensive use of the land in Britain I am delighted to be able to offer the foundation support in understanding the vegetation and history of this special place. My work, gifted as a contribution in kind, has enabled the foundation to be successful in its expression of interest for project funding from the Welsh Government.